A New Book "from" the East

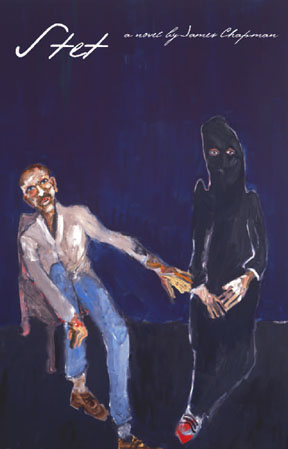

Stet

James Chapman

Fugue State Press

336 pages, $16.00

“Have you ever written a letter to your beloved,” James Chapman asks in his sixth novel, Stet, “and then had to rewrite it repeatedly, trying to please a third party?” I hope you get something from the following...

Chapman’s Stet is the story of a Soviet filmmaker, who is also a Russian filmmaker, who might really be — at least to Authority, and popular opinion — no filmmaker at all. For reasons perhaps only slightly more official than personal, this director Stet has made more movies in his own head, for his own private viewing, than he has on celluloid, for the censorious delectation of the Party and its State. He’s born late in the book (50 or so pages set the stage), suffers at the hands of children, grows up, suffers at the hands of adults, runs afoul of the Nomenklatur for his initial filmic efforts — I'm using "efforts" in the way all reviewers avoid saying films — producing his own type of moving-picture-propaganda, reels for the soul; then, he’s exiled out to a work camp, to be joined by his DP-wife, where they less die than, what else, fade to black. Silencio, that David Lynch line. That, however, is only the surface — an “official” reading, which would also tell you that Stet is an experimental novel, formalist in its manic formlessness, as emotionally tough as concrete in which the characters are cement.

Under the narrative, which is roving in the clean-limbed omniscient tradition of Resurrection Tolstoy mixed with the nervously quick cuts of an American neurotic, say Dos Passos, camera-eye-style encompassing Stalin’s funeral, the composers Shostakovich and Prokofiev, low-level Politburo wonks and post-Communist elinty millionaires, is the autobiography — the author seeming to shine through a chink in the Iron Curtain via allegory, the least postmodern authorial device around.

Enough to say that under the Work, is the Life. And that why autobiography comes to mind is that, ultimately, Stet is art about why Chapman makes art, and an argument for why we lesser lights should make art, too. Stet is the Life and Times of every artist to ever make something “wrong” — in Soviet times “formalist,” “decadent”; in our world, “unmarketable,” “not-reader-friendly” — in the face of everything “right,” which might be symbolized by the Order of Lenin, or the New York Times Bestseller List. (Otherworldly) success, at the end of the book, is nothing less than the gulag.

Which is not to say that Stet is merely reactionary. It’s more like a proofreader’s, or copyeditor’s, “stet” — an editing mark designed to retain the original version of something, scrapping later efforts at change; in pagan Latin meaning “let it stand.” This idea — far from the tropes of “massaging” text, or of fixing everything up in “post-production” — is somewhere between the Beat-Zen “first-thought-best-thought” and the slow acceptance of the self for who and what it is, “becoming comfortable in your own skin.”

Six novels in, it seems that Chapman has made a “career” out of becoming himself — slowly, gorgeously, and as publicly as a small press like his own Fugue State can afford. If he is an undiscovered genius, it’s because genius can only be undiscovered. After that, all is canon, and can be worried apart into schools, influences and intentions. Glass (Pray the Electrons Back to Sand) (1995) was a Gulf War novel as the last Vietnam art, condemning American imperialism in the most intimate terms possible (through faliures of relationship, self-image) while also examining the decadent allure of that alternate America, capitalism's bebop-First Amendment. In Candyland It’s Cool to Feed on Your Friends (1998) was a painful airing of an urbis decayed, semioticized in its ruin to the point where even picking up a spoon to eat your breakfast is an act of performance art, snootily subversive. Daughter! I Forbid Your Recurring Dream! (2000) was softer, quietly madder than anything else that had come before — a coming of age book, an undomesticated portrait of smalltime, small-town nowhere as lived by a woman who was almost incapable of being a “herself” that could adjust to her manifold selves. Stet reprises these responses to the Official Lie, which is universal, in a way that damn near reaches summation on American soil. It is a book written by a mystic in sneakers. And it tells us that if we don’t represent our own damage in art, then all the Job-comforters and their mini-biographers, the armchair dictators of any regime, the squinty presidents and their multinational kitschmeisters will do it for us. They have their red pens to keep their books in the black. We have Stet.