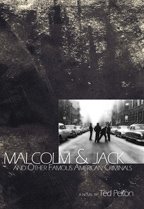

Malcolm & Jack

Malcolm & Jack

(And Other Famous American Criminals)

Ted Pelton

Spuyten Duyvil

262 pages, $14.00

The Beat Generation was really just a bunch of white guys sitting around mothers' houses and cheap rented rooms (in Morningside Heights and the Village, New York City, in suburban Michigan, and elsewhere: Mexico, Paris and Tangiers) according to Ted Pelton's wonderfully demystifying, cartoonishly funny revisionist history cum novel, Malcolm & Jack. Of course, there were a few black people in American then, too, most notably - at least here - a young, angry doper named Malcolm Little, nicknamed Red, later surnamed with only an X.

The Jack of this book is Kerouac, in Pelton's perceptive, dialogue-heavy prose not On the Road but married in the Midwestern hinterlands, reading books in the bathroom of his in-laws, casting around for a subject while the neighbors go to work, have kids, mow the lawn.

Malcolm not yet X flits in and out of Uptown New York college life, in his dealer or drug-running capacity just getting by while the freshmen agonize the extra-curriculum.

Tensions, like "Mosquitoes" in the Faulknerian sense of talkers and planners and thinking-largers, abound.

Pelton does the period magnificently: New York, he says, is a 40s town, and his lens - because a lot of this book lingers like a camera well-handled - zooms in on all the grays and the grillwork, the municipal weight. Kinsey, he of the famous sex poll, shows up as a reincarnation of Freud, who earlier in the book counsels David Kammerer (not smart or attractive enough to be gay as Allen Ginsberg was gay), killed by Lucien Carr after making unwanted advances. Carr runs to Bill Burroughs, ten years his senior, who advises him to get a good lawyer. Kerouac helps Carr bury the weapon. Kammerer sinks into the Hudson. Though many of Pelton's stories retold are well-known, they've never been said better (especially his disquisition on Billie Holiday jailed). Malcolm & Jack is art history pure, as it once was, total story, the oral-thing, returned to the campfire to spark.

As for lasting, it'll last, this book, because it speaks to now beyond all Beatitudinal cliché, in the spirit - and wise, wised-up voice - of what's essentially the American good.

Pelton's got no answers only the questioning tale, and the love that's the right of fellow-traveling, of staying up late with the past.

He marvels along with the reader: America might kill its best artists, but - man - can they ever make art! No consolation, but it's a birthright Pelton's living up to in style.